-------------------------------------------

Most of the colors we see in our everyday lives are from pigments or dyes. Those colors do not change with the direction of the incident light. Common examples of pigments including the green color in leaves (chlorophyll) and the red/orange colors in some sandstones (iron oxide, Fe2O3). Other than plants and minerals, living microbes can also display a wide range of colors by producing different types of pigments. If you have ever been to the Yellowstone national park, the colors displayed at Grand Prismatic Spring are mostly from microbes that generates different types of pigments. These color displays are not affected by the angle of the incident light, as they their working principle is solely based on the chemical structures of the pigment: certain pigment absorbs specific wavelength of light and reflect others back into our eyes. This process is only dependent on the molecular structure of the pigment itself. Take chlorophyll as an example again, it absorbs blue and red light, therefore displaying green color.

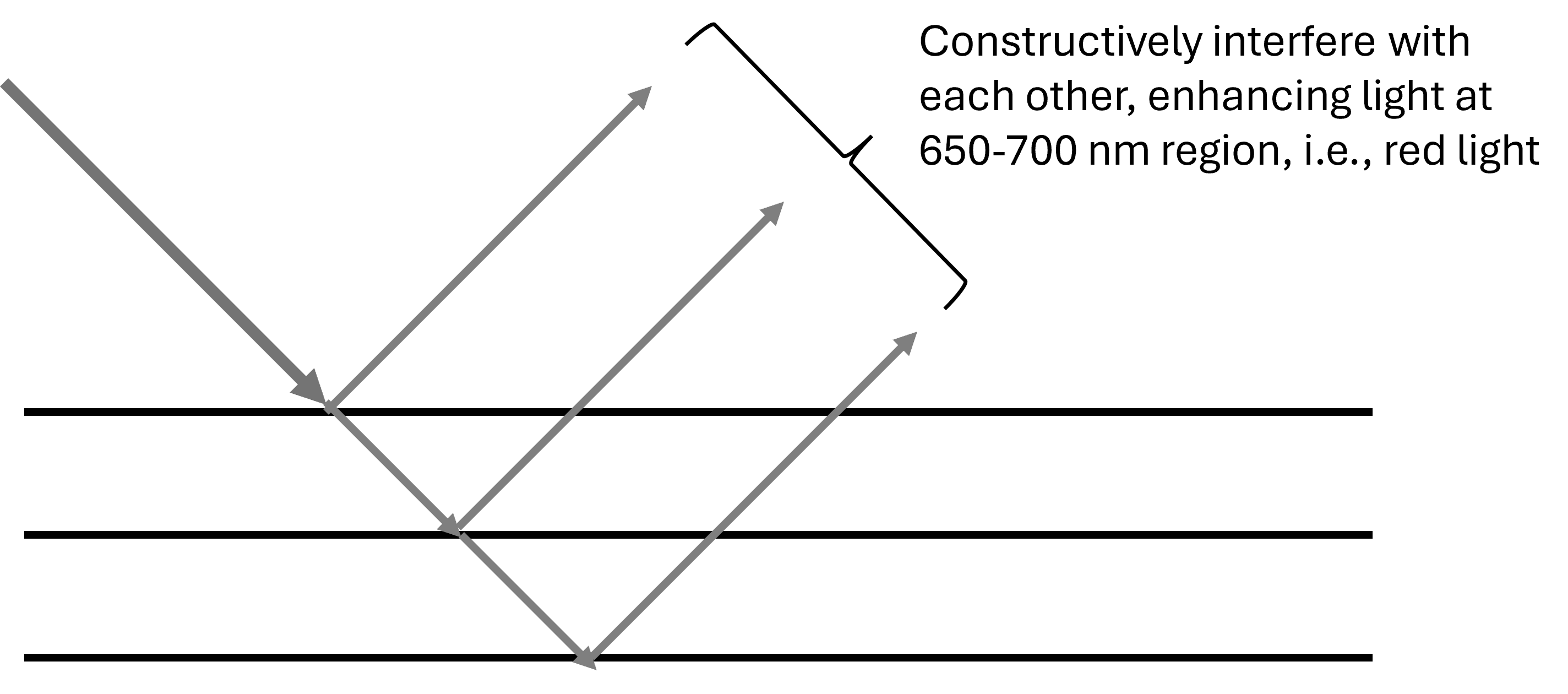

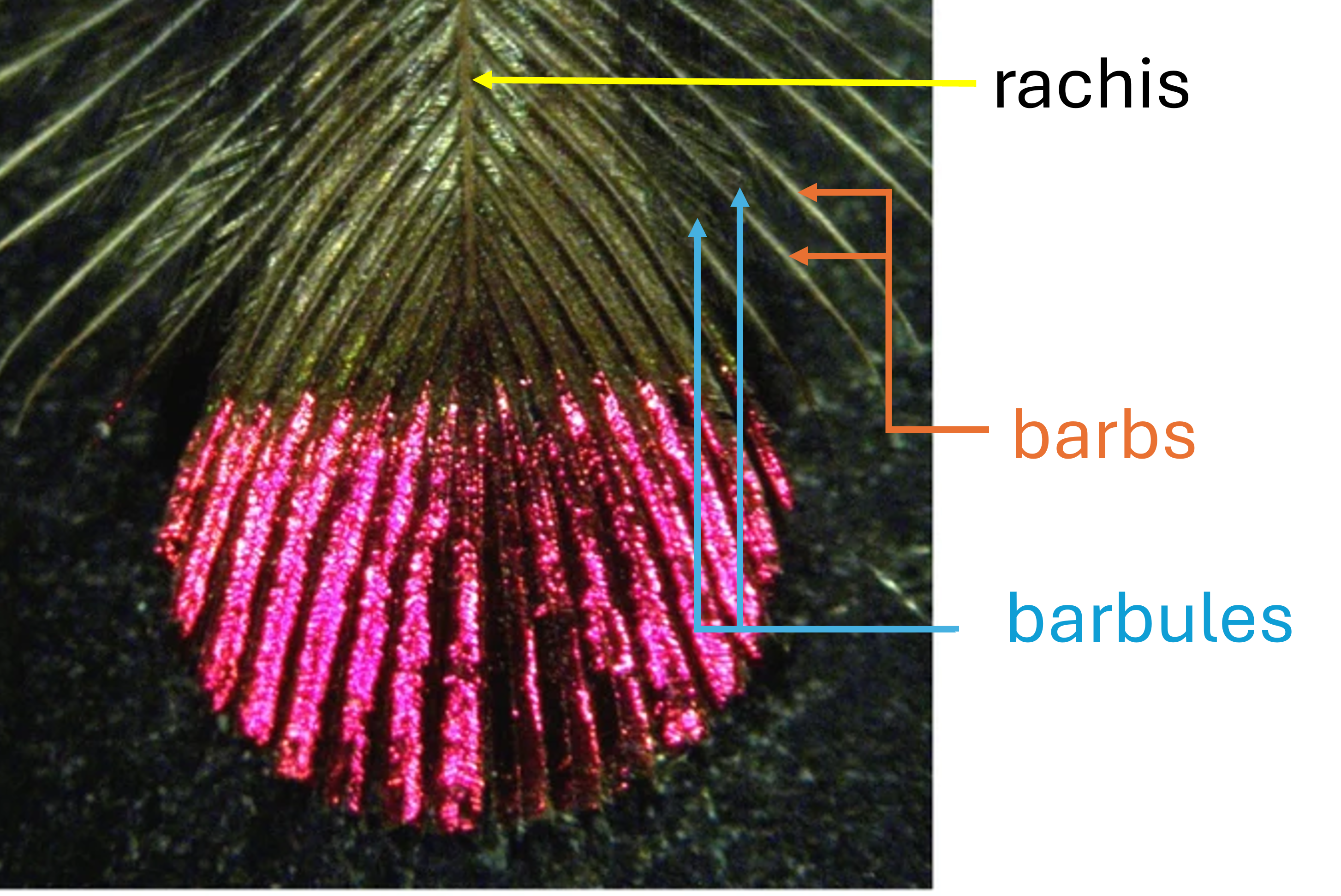

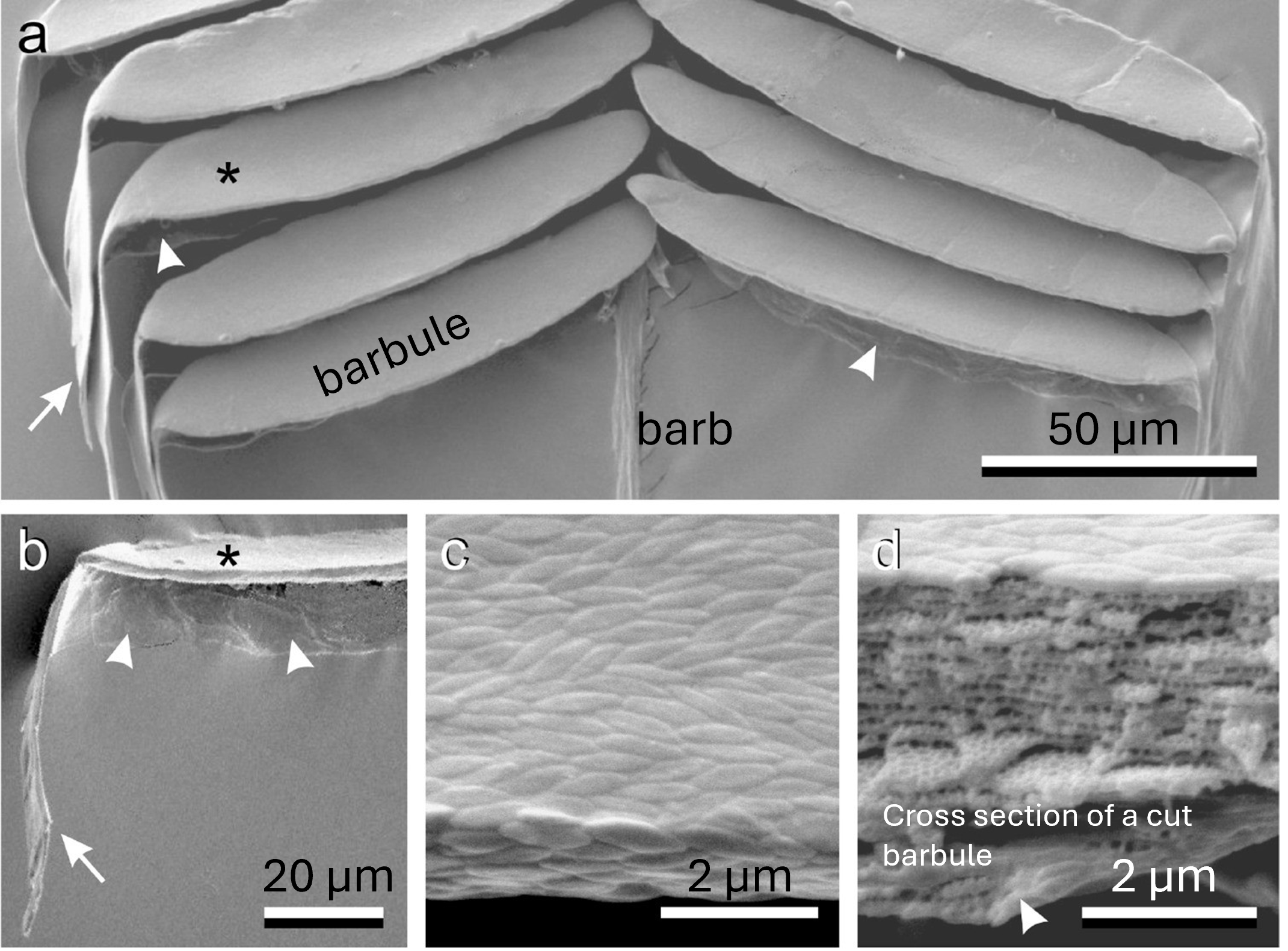

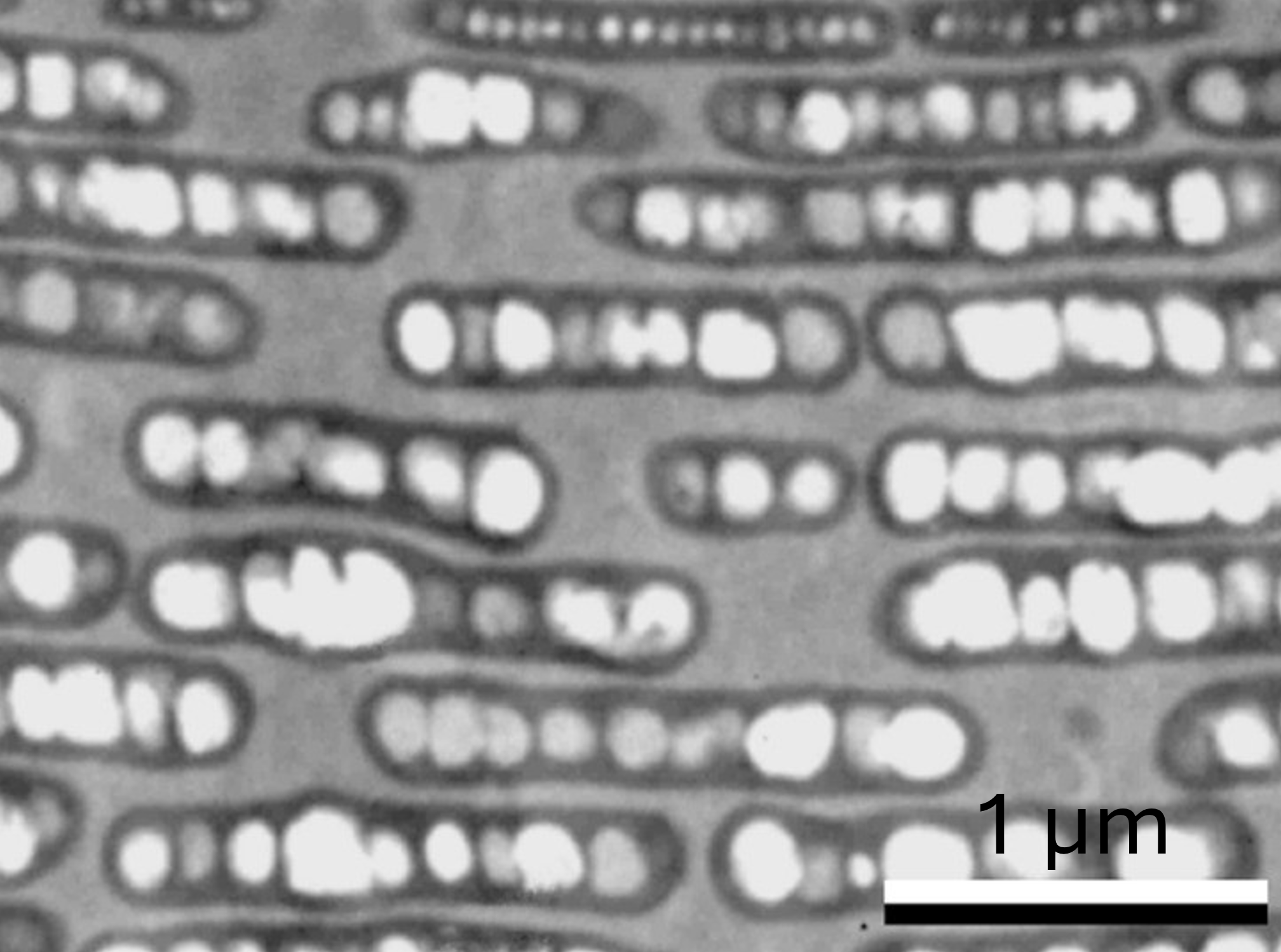

This absorb-and-reflect mechanism explains a large number of colors we see in our everyday lives. However, the light-matter interaction is more complicated than absorption and reflection. They also transmit, scatter, interfere, diffract, etc. Therefore, even without the presence of pigment, one might still see color display through other mechanisms from light-matter interactions. In the context of hummingbird's red neck, light interference is the main reason of this stunning color change. To make the interference happen, hummingbirds developed very unique microstructures in their neck feathers. I unfortunately was not able to get a sample of their neck feather, but found a nice research article revealing this secret in detail. Check the figures below and read the text underneath from left right to understand the structure of the feathers with length scales getting smaller and smaller. All three figures in the panel below are adopted from J Comp Physiol A 204, 965–975 (2018).